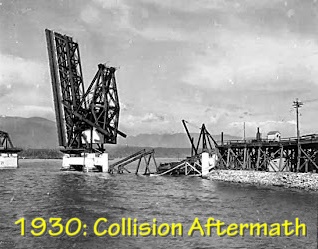

Vancouver is bounded on its north side by a large, deep inlet, ideal for shipping but a serious challenge for road and rail traffic. A series of bridges were built to cope, yet all the while the region (and traffic) continued to grow. Burrard Inlet already had the 1930's Lions Gate Bridge at the First Narrows, but the harbour's second narrows only had a 50-year old 2-lane lift-span to join Vancouver on the south side to North Vancouver opposite. At first, traffic was handled by a low, tilt-span bridge (also called a "bascule" bridge). This might have lasted except for the constant problem of large, heavy ships colliding with the low piers adjacent to the lifting span. In 1930 the bridge was knocked out of service for 4 years while the owner waited for repairs.

Replacement parts and steel had to be shipped from the UK, a slow process. A slightly higher lift-span was added in 1938, but by then ships were larger and heavier, and continued colliding with the now repaired lift-span structure. Something had to be done since traffic was increasing, and repairs and maintenance were overwhelming the bridge owner.

A persistent challenge was out-of-control ships colliding with the bridge and knocking spans into the harbour. Ships were becoming larger and heavier, but they were also not particularly adept at maneuvring through the span-opening in the face of powerful tidal currents. The problem was not going to go away.

After struggling with unending repairs and maintenance, the province made the decision to step in. It was decided to buy and replace the old bridge. The plan was to create a massive new, state-of-the-art, 6-lane bridge across the inlet, that would forever eliminate the tedious delays created when the lift-span had to be raised to let sea traffic pass. Plans were drawn by Swan Wooster Engineers, teams of experienced engineers reviewed the stresses and strains, and Dominion Bridge Company agreed to build it. It was going to be great! A huge, state-of-the-art, steel-arch bridge that would allow Vancouverites to cross back and forth quickly and easily at any time.

Unfortunately, on June 17, 1958, just as the new crossing was about to join hands across the narrows, something went horribly and unexpectedly wrong. The bridge collapsed. The province was stunned that something like this could happen in spite of the dedicated and conscientious work at all levels. Nineteen ironworkers went down in the collapse and drowned, pinned under thousands of tons of bent steel. How would anybody be able to figure out what went wrong after such a disaster?

A film diary was created by Dominion Bridge as a record of work progress. However, Dominion Bridge was not enthusiastic about telling the story of the collapse. A former employee kept the old film record for almost 60 years, and then donated the film to the government of BC for safe-keeping. The film record did not actually help with locating the cause of the failure. There is still an enormous photographic and film record, but only "before and after" the failure event. It was the subsequent Royal Commission (judicial inquiry) and the post-mortem analysis by the American Society of Civil Engineers that uncovered the root cause of the failure that is presented here.

The bridge itself was not an unusual construction project, it was just another gigantic steel span, made of rivetted steel beams and plates, typical of the time. Still, a bridge of this size required a massive amount of engineering analysis and calculation to get off the ground. Somehow, the post-mortem had to uncover what went wrong, even though much of the evidence was entombed 30 feet below the surface of the narrows, hidden in wicked rip-tides and currents. The video below, by the IronWorkers Union, recounts memories of the tragic event.

In 1958, the collapse of the Second Narrows Bridge killed nineteen men. During construction, engineering staff routinely film the construction progress of major projects like this, so investigators were able to reconstruction what led up to the failure. The actual failed element, however, was at the bottom of the sea in a twisted tangle of thousands of tons of bent steel. The challenge was in finding the "source", the actual piece of bent steel that was the one that started the cascade of failures that brought the bridge down.

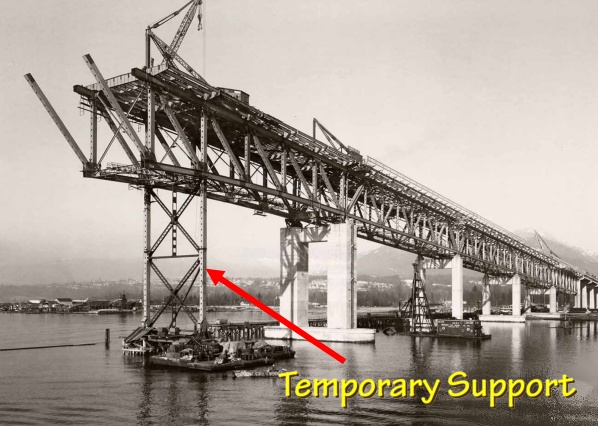

The main arch of the bridge was being constructed from both ends. The standard procedure is to build each end as a cantilever, eventually meeting in the middle. The two ends then, leaning on each other, support the completed arch. During construction, the cantilevered ends are supported on temporary supports called "falsework":

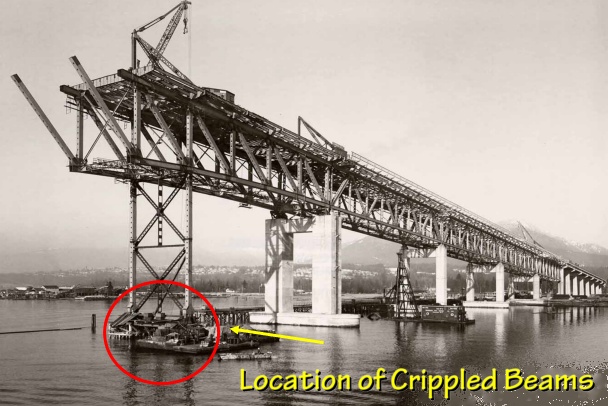

Each cantilever arch was sitting on its own falsework. The false columns were sitting atop a grid of I-beams sitting on temporary footings. The falsework and the I-beams formed a complete support system for the cantilevered spans, and were supposedly designed and inspected by qualified engineering staff.

A post-collapse judicial inquiry, and an analysis by the American Society of Civil Engineers in 2017 showed that the falsework was insufficient to support the spans, and that the engineers had not properly checked the structural math. The result was the I-beams "crippled" under load, allowing the cantilevered structure above to fracture and collapse.

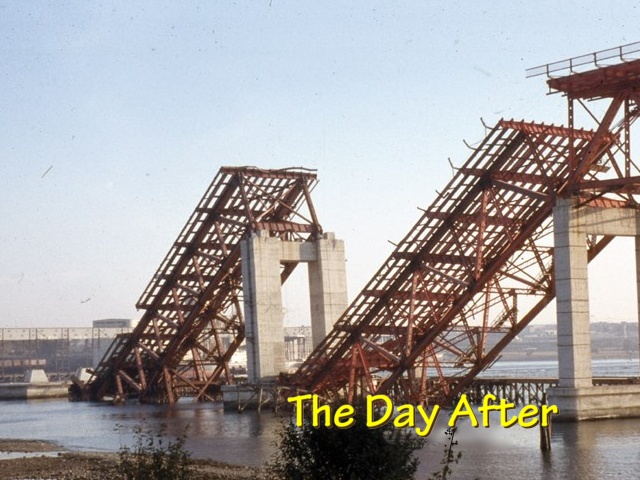

As everybody now knows, the falsework I-beams crippled under load, causing the cantilevered span to separate from its supporting elements, and the bridge was in the water:

It was a tremendously destructive failure. 70 iron-workers were hurled into the narrows, hitting the water at over 100mph. 18 iron-workers were carried to the bottom, most crushed by the following structure. Another died the following day. Some were simply drowned by the weight of their tools and gear. Many were rescued by surviving co-workers, and some by passing boaters. SCUBA-divers did there best to find any survivors, but quickly ran out of time.

Two films have been made of the failure. One, shown below, includes interviews with actual Dominion Bridge employees, and with survivors. The testimony of the Dominion Bridge employees was most important in later engineering studies into the root cause of the collapse, briefly explained above..

"Collapse of the Second Narrows Bridge during Construction" Congress on Technical Advancement 2017 American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) Larry Betuzzi, M.ASCE P.Eng. Senior Engineer, WSP Canada Inc., Edmonton, AB, Canada T5S 2Y3:

Following the collapse, the British Columbia Government established a Royal Commission to examine the cause(s) of the collapse and the lessons learned as a result. After an extensive investigation, it was discovered that a temporary support (called a "false bent" by engineers), designed by an inexperienced engineer and inadequately checked by a senior engineer failed, which led to the collapse of two spans.

Unfortunately, those two design engineers were on the bridge when it failed and both were killed in the collapse. There are many valuable lessons from the Commission Reports related to the roles and responsibilities of contractor’s engineers in their design of the falsework that was intended to support a portion of span number 5 until the structural steel erection had reached Pier 15, and for the responsibilities and duties of engineers in post-disaster inspections and investigations. The ASCE study provides an overview of the collapse and summarizes the effects of the disaster and the findings as to what caused the collapse. Some of these lessons are highlighted in this paper. It was a combination of engineering mistakes, flawed material and procedures, and inappropriate safety standards that resulted in failure. This ASCE paper focuses on failure during construction. In 1994, the bridge was officially renamed the “Ironworkers Memorial Second Narrows Crossing” in honour of the workers who died on that day."